Wearable Technology

Wearables in the Workplace: Real Uses and Emerging Applications

IoT-connected wearable technologies are increasingly being used in a host of industries to monitor workers and improve safety. Chris Lo explores some of the industries already benefiting from their use, and investigates how businesses can incorporate them into their operations

In a modern era in which the digital world is a layer floating above virtually every aspect of life, wearable electronics have become as inevitable as they are innovative.

The ubiquity of smartphones is a fait accompli in the developed world, putting advanced micro-computers and internet access into almost every pocket. It’s not a major leap, in the 21st century, to take the connected features of a smartphone and add them to new devices that can be worn and used hands-free.

Wearable electronics have been around for decades in one form or another, from digital hearing aids to nostalgic fads like the calculator watches that peaked in the mid-1980s.

The modern wave of wearable devices, which has been gathering momentum since the early 2000s, emphasises data-centric innovation and connectivity, spurred by consumer demand for portable Internet of Things (IoT) devices outside of smartphones. This demand has driven the introduction of smartwatches, wearable cameras, fitness-tracking bracelets and eyeglasses capable of adding to reality, or even re-creating it entirely.

From prosumer to professional wearable technology

The modern wearables scene has generally responded to the demand of consumers and glimmers with the sheen of the trendy tech sector, but what about industry? It could certainly be argued that many of these wearable technologies will end up making a far more significant impact on the working world than our leisure time.

There have been many signals pointing to the potential of wearables in the workplace. A 2014 study conducted by London-based Goldsmiths University and cloud computing firm Rackspace tested the performance of 80 office workers over three weeks while using one of three wearable devices. The study concluded that the workers experienced an 8.5% productivity boost, and a 3.5% rise in job satisfaction.

“Using data generated from the devices, organisations can learn how human behaviours impact productivity, performance, well-being and job satisfaction,” said the project’s lead researcher Dr Chris Brauer at the time. “Employees can demand work environments and hours be optimised to maximise their productivity and health and well-being.”

“Using data generated from the devices, organisations can learn how human behaviours impact productivity, performance, well-being, and job satisfaction”

Although the utopian age of wearable tech enhancements in every workplace is still somewhere over the horizon – most employers are conservative when it comes to new tech adoption, and wearables still have a lot to prove – industry is beginning to follow tech-savvy prosumers’ lead when companies feel there are true benefits on offer.

Big data innovations and IoT – often called the industrial internet in the enterprise context – are already making a big splash in industry, especially in process-oriented sectors such as heavy industry and manufacturing, and wearables are a physical extension of that trend.

Recently-published research by Technavio is positive on IoT-enabled wearables’ prospects in industrial applications, predicting a 10% compound annual growth rate between 2017 and 2021.

Image courtesy of RealWear

A safe pair of hands: the safety benefits of wearables

Of all the potential benefits offered by wearables to industries, enhanced safety has been the easiest sell. IoT-enabled wearable devices are increasingly becoming part of forward-thinking companies’ efforts to keep their workers safe in risk-intensive roles. Australia-based SmartCap Technologies, for example, has seen strong demand from the mining and long-distance logistics sectors for its Life by SmartCap system.

The technology includes the LifeBand, which can be fitted to the inside of a hardhat, cap, beanie hat or other headwear, and monitors brainwaves for signs of exhaustion and the ‘microsleeps’ that can be deadly if the user is driving a long-haul truck or operating heavy machinery.

The device sends notifications to the wearer in real-time before the symptoms of fatigue develop, allowing the user to manage their own fatigue. Individual reporting through an associated smartphone app also allows users to learn more about what times of day they are most alert and most fatigued.

In May, SmartCap announced a partnership with another safety tech company, Toronto-based Newtrax Technologies, to further adapt the technology for underground mines.

“IoT-enabled wearable devices are increasingly becoming part of forward-thinking companies’ efforts to keep their workers safe in risk-intensive roles”

The flexibility of wearables is reflected in the wide range of form factors offering IoT-enabled safety enhancements to workers. SoloProtect ID, which connects lone workers to a support centre and transmits GPS data for assistance in case of an injury or threat of violence, is presented as an identity badge. The MIT Design Lab, meanwhile, partnered with oil company Eni to produce a range of wearable safety solutions under the banner of ‘Safety++’. Items include a toxic substance-detecting jacket, shoes that monitor the weight of carried loads, and an undershirt that uses tactile communication to notify the user when one of those sensors flags an issue.

Limitations around the sophistication and nuance a wearable device can make sense of in safety-critical situations and automated emergency response, are likely to be a busy avenues for future development.

“You will see notifications about some kind of event happening but we are not at the point where a wearable will detect something and allow something else to happen as a result,” International Data Corporation wearables research manager Ramon T Llamas told the Financial Times in October.

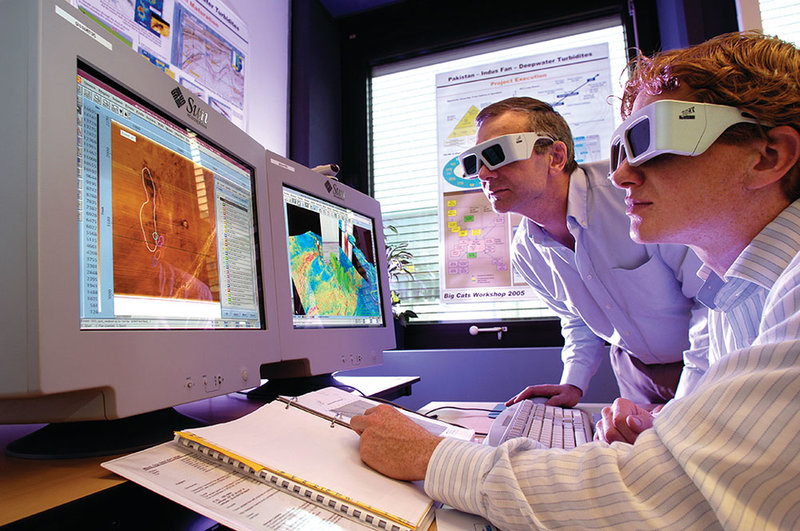

Image courtesy of Royal Dutch Shell

The augmented workforce

While wearable safety technologies have entered the industrial mainstream, with hundreds of thousands of users worldwide, companies have been slower to open the doors to wearables in their day-to-day operations, like, say, manufacturing or operations and maintenance. Unlike the living room or the office, many industrial environments present the kinds of risks that necessitate stringent checks to ensure any new wearable tech isn’t a fire risk on an offshore oil platform or a chemical plant, and can stand up to extreme conditions.

“Wearable technology will have to survive extremes of temperature, from over 60°C in the deserts of Iraq to -50°C in the winters of Alaska,” said BP technology principal Blaine Tookey at the 2016 Wearable Technology Show.

The stakes are higher, too: if novel technologies fail unexpectedly, production downtime can cost millions, so there’s a natural inclination towards iterating on proven systems rather than trying to reinvent the wheel.

Nevertheless, deploying wearables in a strategic, well-controlled way is packed with potential that is only beginning to be explored. In a November editorial for Computer Business Review, Zebra Technologies senior manufacturing manager for EMEA David Stain noted that two in five manufacturers are planning to increase capital investment in wearables by 2022.

“Wearable technology will have to survive extremes of temperature, from over 60°C in the deserts of Iraq to -50°C in the winters of Alaska”

“Many firms are willing to take the plunge,” Stain wrote. “They say they will increase the deployment of wearable technology by 15% over the next five years because they want to increase real-time monitoring across production. Companies say monitoring will rise from 7% to 21% in order to improve quality assurance. Wearables will offer opportunities to increase productivity on the plant floor, as well as improve safety.”

Wearables can also act as a multiplier of expertise through digital communication. At Maersk Oil’s in-development Culzean gas condensate field in the North Sea, due to start production in 2019, the company is testing augmented reality (AR) glasses, allowing workers to open operating records for tagged equipment whenever they are nearby.

“If [a worker] sees a problem or an anomaly, he’ll be able to call up a support facility onshore with experts,” Maerk Oil’s head of corporate technology and projects Troels Albrechtsen told Offshore Technology last year. “They can be in his ear, seeing the video stream of what he sees live, and provide him with live feedback on how he can best tackle that issue.”

As companies’ wearable ambitions grow, purpose-built devices are appearing on the market to meet the demand. Earlier this year, Vancouver-based RealWear launched the HMT-1 wearable computer, which was designed specifically for industrial users. This rugged, head-mounted tablet computer is controlled by voice commands, facilitating hands-free access of technical documents, complete work orders and, similarly to Maersk’s testing, remote video streaming to connect an on-site worker with remote experts.

In spite of the challenges involved in bringing connected wearable technologies to heavy industry – cost, complexity, conditions – the lure of long-term efficiency benefits and cost savings is likely to be enough of a draw for an increasing number of parties in heavy industry, and the potential will only grow as automation and digitisation continue to transform these industries.

But in safety-critical environments, it all depends on the implementation. Technology rewards those who act first, some say, but in the case of IoT-enabled industrial wearables, the biggest benefits may go to those who think before they act.

Image courtesy of Smallworldsocial